Among the many fundamental questions that science asks about the origins of life, one of the deepest concerns the existence of a common point from which all living organisms descend. This point is neither mythological nor philosophical, but biological and well-defined: it is referred to by the acronym LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor. LUCA represents the organism—or more accurately, the population of organisms—from which all forms of life on Earth today descend, from the simplest bacteria to humans.

It is important to clarify from the outset what LUCA is not. LUCA is not the first form of life to appear on the planet and should not be imagined as a single isolated “primordial cell.” On the contrary, it is the result of a long preceding phase of chemical and biological evolution, during which increasingly complex molecules began to organize, replicate, and compete. LUCA represents the oldest point in the tree of life that we can reconstruct with reasonable certainty through comparative genetics.

Indeed, all living organisms share a set of features so deep and specific that they can only be explained by a common origin. The genetic code, which determines how sequences of nucleotides are translated into proteins, is practically universal. Ribosomes, the cellular structures that synthesize proteins, operate according to the same principle in every known form of life. Key basic metabolic pathways, such as those involved in energy production, show remarkable similarities even among evolutionarily distant organisms. All of this indicates that LUCA already possessed a sophisticated and well-structured biochemistry.

In temporal terms, LUCA is placed between 3.8 and 4 billion years ago, at a time when Earth was a young, geologically unstable planet, with an atmosphere lacking free oxygen. Oceans were already present, volcanism was intense, and chemical energy was abundant. In this context, LUCA would have been an anaerobic organism, unable to utilize oxygen, which would only become common hundreds of millions of years later with the advent of oxygenic photosynthesis.

Genetic evidence suggests that LUCA lived in an aquatic environment and was probably associated with submarine hydrothermal vents. These environments, still present on the ocean floor today, provide particularly favorable conditions for the chemistry of life: liquid water, an abundance of minerals, temperature gradients, and chemical potential gradients capable of supplying continuous energy. In a primordial world lacking sunlight penetration into the deep oceans, chemical energy was a crucial resource.

One of the most fascinating aspects of LUCA is that, despite being extremely ancient, it was by no means “simple” in the common sense of the term. To be the ancestor of all modern life forms, LUCA must have already possessed a system for replicating genetic information, likely based on DNA or a combination of DNA and RNA, as well as a molecular apparatus for protein synthesis. This implies that the true origin of life predates LUCA and that the earliest stages, often described with the RNA world hypothesis, were an evolutionary laboratory lasting millions of years.

LUCA thus represents a kind of evolutionary “bottleneck.” Many primitive life forms could have arisen independently during Earth’s early eras, but only one evolutionary line left descendants up to the present. All other biological experiments disappeared without leaving direct traces. In this sense, LUCA is not only an ancestor but also a silent witness of the oldest natural selection, the process that established the fundamental rules of life on Earth.

The study of LUCA is important not only for understanding our past but also has profound implications for astrobiology. If the fundamental characteristics of LUCA—such as the use of water as a solvent, carbon-based chemistry, and molecular replication mechanisms—are the result of universal physical and chemical laws, then similar life forms could emerge elsewhere, on planets with analogous conditions. In this sense, LUCA becomes an interpretative key not only for life on Earth but for life in the universe.

In short, LUCA is neither a fossil nor an organism we can directly observe, but a powerful scientific reconstruction obtained by integrating genetics, biochemistry, geology, and physics. It is the deepest point we can trace in the story of life and represents the moment when matter, guided by the laws of nature, definitively crossed the threshold separating chemistry from biology.

How LUCA Was Identified and How Certain We Are of Its Existence

LUCA was not “discovered” in the traditional sense: there are no fossils, physical remains, or direct traces of this ancient ancestor. Its identification is the result of extensive indirect reconstruction, based on one of the most powerful tools of modern science: genetic and molecular comparison across all living beings. LUCA is therefore a scientific deduction, not a specimen, but a deduction founded on extraordinarily robust evidence.

The idea of a universal common ancestor dates back to Darwin, but remained purely theoretical until the second half of the 20th century. The breakthrough occurred when biology began to study life not only anatomically or physiologically but also at the molecular level. With the discovery of DNA’s structure and, especially, the development of sequencing techniques, it became possible to directly compare the fundamental “texts” of life: genes, RNA, and proteins.

Analyzing these data, biologists discovered something remarkable. All known organisms, without exception, use the same genetic code, based on the same four nucleotide bases, translated through the same molecular mechanism. Even more significant is that certain structures, like ribosomes, have regions so conserved that they are nearly identical in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. Such similarities cannot be explained by convergent evolution or mere chance—they clearly indicate a common origin.

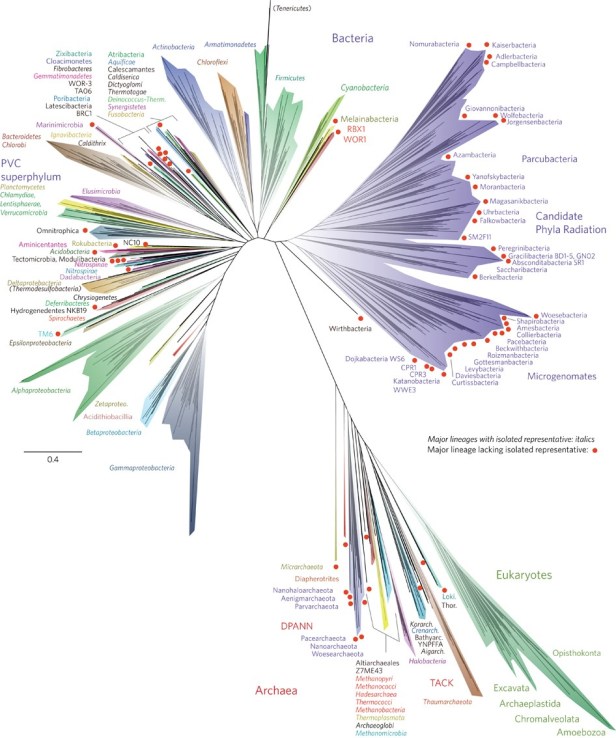

The decisive step comes with the construction of molecular phylogenetic trees. By comparing differences and similarities in genetic sequences, it is possible to reconstruct evolutionary relationships among organisms, much like building a family tree from surnames and historical documents. When these trees are constructed using essential genes involved in fundamental life processes, all evolutionary lines converge toward a single deep point in time. That point is what we call LUCA.

A crucial aspect is that this convergence emerges independently across numerous studies, conducted with different methods and on different molecules. Whether analyzing ribosomal RNA, metabolic enzymes, or genes involved in DNA replication, the result is the same: there is a common root. This makes the LUCA hypothesis extremely robust from a scientific standpoint.

Of course, this does not mean we know LUCA in every detail. Science carefully distinguishes between what is certain and what is inferred. We are confident that all current life shares a common ancestor, because alternatives would be incompatible with the universality of the genetic code and the shared molecular architecture. We also know that this ancestor was already biologically complex, with a replication system, genetic translation machinery, and organized metabolism. On other aspects, such as its exact cellular structure or precise environment, well-founded but non-definitive hypotheses exist.

It is important to note that LUCA does not imply that only one primordial life form existed. On the contrary, it is very likely that in the first hundreds of millions of years of Earth’s history, many primitive life lines emerged, based on similar but not identical chemistries. Most of these lines went extinct without leaving descendants. LUCA represents the only evolutionary line that overcame all environmental and evolutionary bottlenecks, becoming the ancestor of every current organism. In this sense, LUCA is a historical and evolutionary concept, not an instantaneous event.

As for the certainty of its existence, in evolutionary biology LUCA is considered one of the most solid concepts. Questioning LUCA would require explaining how extremely complex molecular structures, identical in detail, could have arisen independently multiple times—a hypothesis that contradicts what we know about the laws of chemistry and evolution. For this reason, LUCA’s existence is considered virtually certain, even if its precise form remains the subject of ongoing research.

Ultimately, LUCA is not a hypothetical figure in the weak sense, but a logical necessity imposed by the data. It is the most remote point we can trace using scientific tools, the common foundation on which the entire terrestrial biosphere rests. Understanding it means understanding not only where we come from, but also which aspects of life could be universal wherever conditions allow life to emerge in the universe.

Was There Life Before LUCA?

Yes, it is highly likely that something existed before LUCA, and this is one of the strongest conclusions of origin-of-life biology. LUCA, the Last Universal Common Ancestor, does not represent the beginning of life, but the most distant point in biological evolution that we can reconstruct with confidence. The very fact that LUCA was already a complex biological system implies the existence of a long preceding phase in which matter gradually acquired the properties we now associate with life.

In the first hundreds of millions of years after Earth’s formation, the planet was a profoundly different environment. Oceans had already formed, volcanism was intense, and the atmosphere lacked free oxygen. In this energy-rich context, chemistry operated continuously. Simple organic molecules, such as amino acids, sugars, and nitrogenous bases, could form spontaneously on Earth or be delivered from space. This phase, known as prebiotic chemical evolution, was not yet life, but constituted the fertile ground from which life could emerge.

The crucial step occurred when some of these molecules began to behave in new ways, acquiring the ability to replicate. The appearance of molecular replicators marks a fundamental conceptual threshold: for the first time, a primitive form of natural selection comes into play. Molecules that replicated more efficiently became more abundant, while others disappeared. In this phase, the boundary between chemistry and biology becomes blurred. Life, in the strict sense, was not yet fully present, but it was no longer merely inert chemistry.

The most widely accepted hypothesis for this stage is the so-called RNA world. RNA is extraordinary because it can perform a dual function: storing genetic information and catalyzing chemical reactions. Before the existence of DNA and proteins, systems based primarily on RNA could sustain imperfect replication cycles, accumulating variations upon which selection could act. This suggests that before LUCA, much simpler biological systems existed, but they were already subject to evolutionary dynamics.

A further step toward true biology was the spatial organization of these systems. In aqueous environments, lipid molecules can spontaneously self-assemble into vesicles, structures resembling tiny bubbles. When these vesicles enclosed replicating molecules, so-called protocells were born. These entities were not yet cells in the modern sense but introduced a fundamental concept: compartmentalization. Separating an “inside” from an “outside” made selection more effective and allowed the emergence of a primitive form of biological individuality.

Pre-LUCA Earth may have been populated by a mosaic of different protocells, based on different chemistries, some of which are now completely lost. There is no reason to think that life had a single linear origin. On the contrary, many parallel evolutionary experiments likely existed, most of which went extinct without leaving descendants. LUCA represents the line that, through a favorable combination of stability, efficiency, and adaptability, succeeded in overcoming all environmental and evolutionary bottlenecks.

The fact that LUCA already possessed a complex genetic system, organized metabolism, and a molecular apparatus for protein synthesis demonstrates that it could not have been the first living organism. Rather, it is the result of a long preceding history, perhaps lasting tens or hundreds of millions of years, during which matter gradually learned to copy itself, organize, and evolve.

We have no direct evidence of this pre-LUCA phase, because the systems involved were microscopic, fragile, and lacked fossilizable structures, and because the early Earth surface has been profoundly reshaped by geology. Nevertheless, the totality of indirect evidence—from prebiotic chemistry, molecular biology, and evolutionary logic—makes the existence of a pre-LUCA phase not only plausible but practically inevitable.

In this sense, LUCA marks the moment when life becomes continuous, inheritable, and unbroken up to the present. Before LUCA, life was an emerging, unstable, experimental process; after LUCA, it becomes a unique and branching evolutionary history that leads directly to all the biodiversity we know today.