When discussing the great scientific insights of antiquity, the name of Eratosthenes of Cyrene occupies a place of honor. Living in the 3rd century BCE, librarian of the magnificent Library of Alexandria, mathematician, astronomer, and geographer, Eratosthenes was the first to measure the circumference of the Earth with remarkable accuracy. But even before that, he provided a quantitative, experimental demonstration of the spherical nature of our planet, at a time when this idea was far from universally accepted.

Historical context: did people really think the Earth was flat?

In the educated Greek world, the idea of a spherical Earth had been circulating for centuries: philosophers such as Pythagoras, Parmenides, and Aristotle had argued for sphericity based on qualitative observations — the Earth’s shadow on the Moon during lunar eclipses, the changing sky as one moved north or south, the curvature of the horizon seen when ships sailed away.

However, their knowledge was still more speculative than scientific in the modern sense. No one had quantitatively demonstrated how large this sphere was. Moreover, outside philosophical circles, the common conception remained uncertain and often flat.

With a blend of theory and experiment, Eratosthenes placed the matter on measurable ground.

Eratosthenes’ experiment: a masterpiece of simplicity and insight

His entire reasoning relied on facts recorded in the archives of the Library of Alexandria:

- In the city of Syene (modern Aswan), on the day of the summer solstice at noon, the Sun could be seen reflected at the bottom of deep wells. This happened because the Sun stood directly overhead.

- In Alexandria, farther north, at the same moment of the year, the Sun was not perfectly perpendicular: vertical objects cast a shadow.

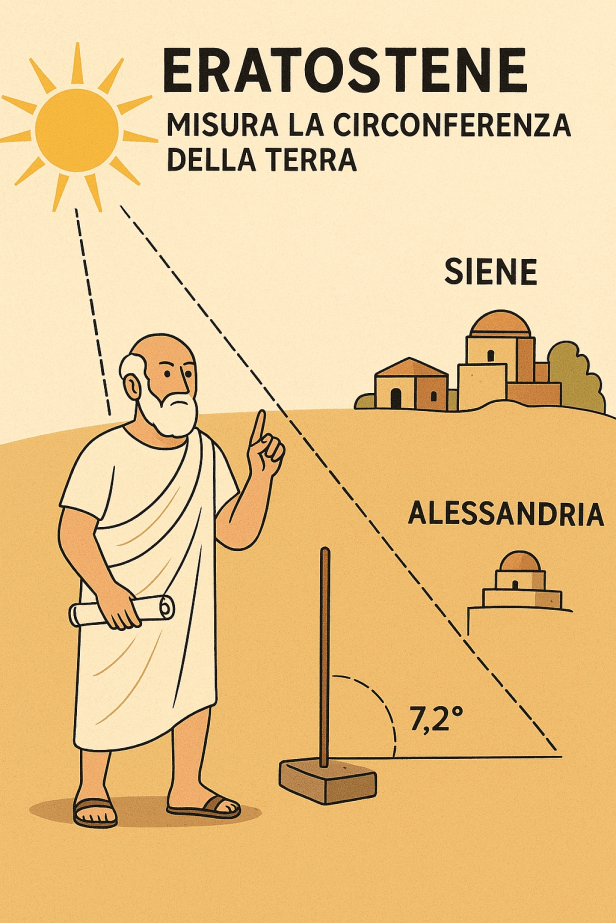

Eratosthenes’ idea was brilliant in its simplicity: if the Earth were flat, the angle of sunlight would be identical everywhere. But the fact that the Sun stood at the zenith in Syene and not in Alexandria could only be explained by assuming a curved surface.

Measuring the angle

Eratosthenes placed a gnomon (a vertical rod) in Alexandria and measured the shadow it cast at noon on the solstice. He obtained an angle of about 7.2 degrees, approximately one fiftieth of a full circle (360 degrees). In other words: the segment of the meridian between Alexandria and Syene represented 1/50 of the Earth’s entire circumference.

The distance between the two cities

The distance was known thanks to measurements made by the bematists, the surveyors of the time. It was estimated at about 5,000 stadia (roughly 800 km, according to the most accepted conversion).

The final calculation

If 5,000 stadia correspond to 1/50 of the circumference:

Circumference of the Earth = 5,000 × 50 = 250,000 stadia,

which translates to a value between 39,000 and 46,000 km, depending on the length of the stadium used.

The real value is 40,075 km: an extraordinarily accurate result for the 3rd century BCE.

Implications and consequences of the discovery

Reception in the ancient world

Eratosthenes’ work was admired by many learned contemporaries, although some critics emerged: the geographer Posidonius contested the distance used in the calculation and obtained a smaller estimate (incorrect, but more popular for centuries).

Nevertheless, among scholars, the Earth’s sphericity became accepted scientific fact rather than mere philosophical speculation.

Impact on science and geography

Eratosthenes’ contribution was revolutionary for several reasons:

- it laid the foundations for geography as a quantitative science

- it introduced fundamental concepts such as meridians and parallels

- it enabled more refined astronomical calculations

- it provided a measurement that remained the most accurate available for many centuries

From glory to temporary obscurity

With the decline of Greco-Roman culture, many scientific works were lost or misunderstood. Although the idea of a spherical Earth survived in astronomical traditions, it became less present in everyday knowledge. Only during the Renaissance and the great oceanic explorations did the work of Eratosthenes regain full recognition.

The strength of the scientific method

Eratosthenes’ experiment is a shining example of how observation, logic, and geometry can lead to profound scientific truths without the need for complex instruments. His measurement of the Earth’s circumference was not just a mathematical achievement: it was a demonstration of method, a timeless invitation to look at the world with curiosity and rationality.