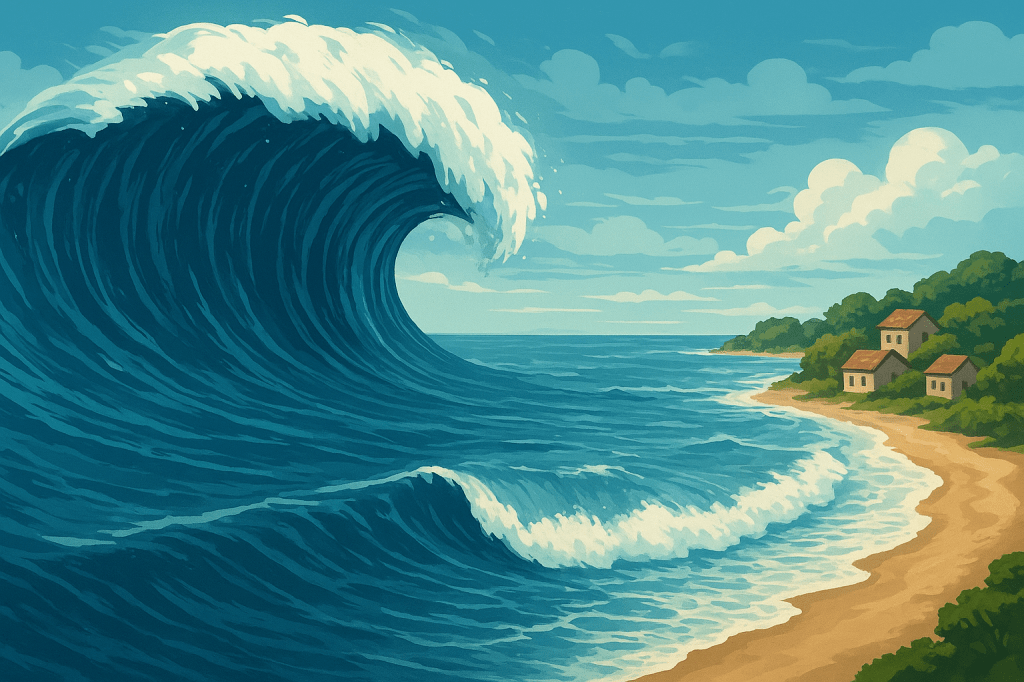

When we hear the word tsunami, we immediately picture towering walls of water crashing onto the shore with devastating force. But what makes this natural phenomenon truly fascinating — and unsettling — is how it forms and transforms: an almost invisible wave in the open ocean that becomes an uncontrollable fury as it nears the coast.

The Origins of a Tsunami

A tsunami (from the Japanese tsu, “harbor,” and nami, “wave”) does not originate from the wind like ordinary sea waves, but from a sudden displacement of a large mass of water. The main causes are:

- Submarine earthquakes: when a fault line suddenly shifts along the ocean floor, the Earth’s crust can rise or sink by several meters. The overlying water is pushed upward and begins to spread in all directions.

- Volcanic eruptions: the explosion or collapse of an underwater volcano can have the same effect.

- Landslides and glacier collapses: large masses of rock or ice plunging into the sea can displace enormous volumes of water.

- Meteorite impacts: a very rare but potentially catastrophic event, such as the asteroid that struck the Yucatán Peninsula 66 million years ago.

A Silent Giant in the Open Ocean

In the middle of the ocean, a tsunami is almost imperceptible. Its height may be only 50 centimeters or a meter, but its wavelength — the distance between two crests — can reach hundreds of kilometers. Thanks to this immense wavelength and the ocean’s depth, the wave can travel at incredible speeds, up to 800–900 km/h — comparable to a jetliner — without losing energy.

A ship in deep water would hardly notice its passage: the wave crosses the ocean as a slow, gentle rise and fall of the sea surface.

What Happens Near the Coast

As the tsunami approaches the shore, everything changes. The seabed becomes shallower, and the wave — slowing down — becomes compressed: its energy, forced into a smaller volume, is transformed into height. It’s as if the same amount of water had to lift itself upward to find space. Thus, a one-meter wave in the open sea can become a wall of water 10, 20, or even 30 meters high when it reaches the coast.

Moreover, tsunamis do not consist of a single wave but of a series of waves arriving minutes or even hours apart. Often, the second or third wave is the most destructive.

Different from Wind Waves

Ordinary sea waves are caused by the wind transferring part of its energy to the surface of the water. Their wavelengths are just a few meters, and their periods only a few seconds.

Tsunamis, by contrast, involve the entire water column, from the seabed to the surface, and their period can exceed 20 minutes. They are not simple ripples on the surface but immense masses of ocean water moving as a single body.

Tsunami Records

- Highest wave ever recorded: the record belongs to the Lituya Bay megatsunami in Alaska, on July 9, 1958. A landslide crashing into a fjord produced a wave that reached 524 meters (1,720 feet) — as tall as a 170-story skyscraper.

- Fastest speed recorded: tsunamis can travel at up to 900 km/h (560 mph) in deep ocean waters, though most move between 600 and 800 km/h.

- Most destructive: the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 26, 2004, caused by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake, killed over 230,000 people in 14 countries. Waves reached 30 meters (98 feet) in some coastal areas.

A Natural but Predictable Phenomenon

Today, thanks to networks of underwater sensors and satellites, tsunamis can be detected and reported within minutes. However, prevention and awareness remain vital: recognizing warning signs — such as an unusually sudden retreat of the sea — can save many lives.

How the Speed of a Tsunami Is Calculated

The speed of a tsunami wave is not measured like that of a car or an airplane — with radar or a stopwatch — but calculated from physical laws describing wave motion in deep water.

The Basic Physical Formula

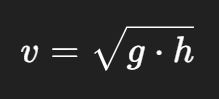

The propagation speed of a tsunami depends only on the ocean’s depth:

where:

- g = acceleration due to gravity (≈ 9.81 m/s²)

- h = ocean depth (in meters)

This formula applies because tsunamis are gravity waves in deep water, meaning that the entire column of water, not just the surface, moves together.

A Practical Example

Suppose the ocean is 4,000 meters deep. This generates a speed of about 713 km/h (443 mph) — which explains why tsunamis in the open sea can travel between 700 and 900 km/h.

If the depth decreases to 100 meters near the coast, the speed drops to about 112 km/h (70 mph).

As the water gets shallower, the wave slows down, but its energy remains — so its height increases dramatically.

How It’s Measured in Reality

Modern instruments allow scientists to measure and confirm tsunami speeds in real time, using networks of sensors and satellites:

- DART buoys (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis): anchored to the seabed, these buoys record pressure variations caused by passing waves. When they detect an anomaly, they send a signal via satellite. By comparing arrival times between multiple buoys, scientists can calculate the wave’s actual speed.

- GPS and radar altimetry satellites: these can detect tiny variations in sea level — just a few centimeters — across open oceans, allowing the wave’s speed and shape to be mapped.

- Coastal tide gauges: they record the arrival of waves near shore and, combined with buoy data, allow highly precise tracking of tsunami propagation.

Why Speed Matters

Knowing a tsunami’s speed is crucial for early warning systems: by estimating how long it will take to reach the coast, scientists can calculate how much time remains for evacuation.

For instance, if a tsunami originates off Japan and travels at 700 km/h, it can take about 10 hours to cross the Pacific Ocean and reach the American coastline.