The universe is filled with secrets, some hidden in the vastness of space and others embedded in light itself. One of the most profound remnants of the early universe is the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation – a faint, nearly uniform glow that fills the cosmos. Discovered more than half a century ago, this ancient light offers a direct window into the infancy of the universe, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Understanding the CMB has transformed our view of the cosmos, revealing its age, composition, and evolution.

A Snapshot of the Early Universe

To understand the CMB, we must journey back to the universe’s earliest moments. The Big Bang, approximately 13.8 billion years ago, marked the beginning of space, time, and matter. In the first fractions of a second, the universe expanded at an incredible rate – a process known as cosmic inflation. During this period, the universe was a hot, dense plasma of charged particles and photons (light).

In this primordial soup, photons continuously interacted with protons and electrons, preventing light from traveling freely. However, as the universe expanded and cooled, it reached a critical temperature of -270.4 degrees Celsius, allowing protons and electrons to combine into neutral hydrogen atoms. This process, called recombination, freed the trapped photons, allowing them to travel unimpeded. These photons are what we now detect as the CMB.

Discovery of the CMB

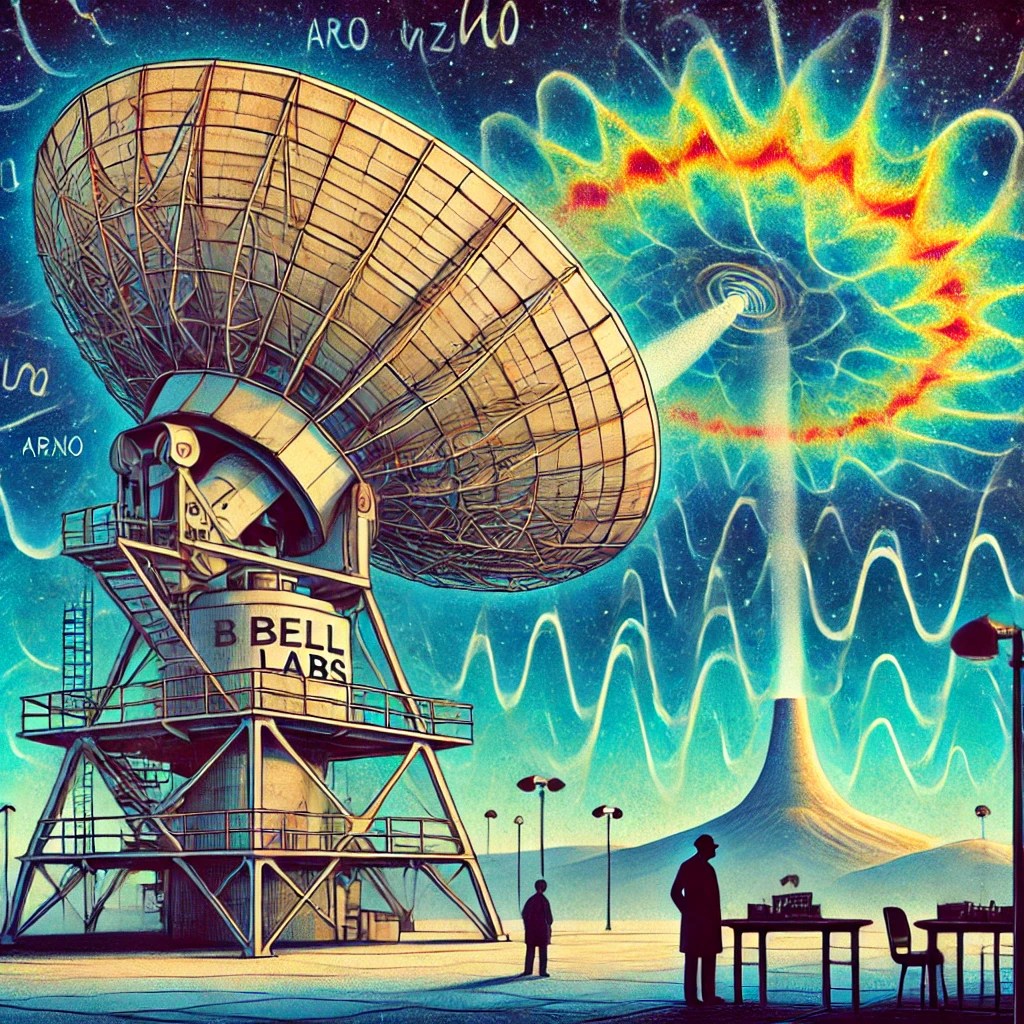

The existence of the CMB was first theorized in the 1940s by physicists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman, following George Gamow’s work on the Big Bang. However, it wasn’t until 1965 that Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, two radio astronomers working at Bell Labs, accidentally discovered the CMB. They were trying to eliminate background noise from a sensitive microwave receiver when they stumbled upon a persistent, isotropic signal that they could not explain. At first, they thought the noise might be due to pigeon droppings inside the antenna. After removing the pigeons (and cleaning the droppings), the mysterious signal remained.

Unbeknownst to Penzias and Wilson, a team of Princeton physicists led by Robert Dicke had been searching for exactly this radiation as a confirmation of the Big Bang theory. When the two groups connected, the importance of the discovery became clear. Penzias and Wilson went on to win the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics for their serendipitous detection of the CMB.

The Spectrum and Temperature of the CMB

The CMB is the most perfect blackbody radiation spectrum ever observed. Its temperature is remarkably uniform, measured at -270.4°C. However, tiny temperature fluctuations on the order of microkelvins provide critical clues about the structure of the universe.

These fluctuations, mapped with extraordinary precision by satellites such as COBE (Cosmic Background Explorer), WMAP (Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe), and most recently, Planck, reveal the seeds of cosmic structures. Slight density variations in the early universe were amplified by gravity over billions of years, eventually forming the galaxies, stars, and planets we see today.

The CMB and the Composition of the Universe

The detailed study of the CMB has provided a cosmic recipe for the universe. From precise measurements, scientists have determined that ordinary matter (atoms) makes up only about 4.9% of the universe’s total energy density. Dark matter, an unknown form of matter that does not emit or absorb light, accounts for approximately 26.8%, while dark energy, a mysterious force driving the accelerated expansion of the universe, constitutes about 68.3%.

These findings come from observing the CMB’s anisotropies – minute variations in temperature and polarization – which encode information about the universe’s geometry and expansion history.

A Glimpse into the Future

Future missions and ground-based observatories continue to study the CMB with increasing sensitivity. Projects like the South Pole Telescope and the Atacama Cosmology Telescope aim to probe the polarization patterns of the CMB to understand the era of cosmic inflation better. Detecting primordial gravitational waves imprinted on the CMB could provide direct evidence of inflation and offer insights into the fundamental physics that governed the universe’s birth.

The cosmic microwave background is one of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting the Big Bang model. Its discovery and subsequent study have revolutionized our understanding of cosmology, transforming speculative theories into precise science. As technology advances, the CMB continues to whisper its secrets to those who listen, guiding humanity closer to answering the most profound questions about the origin and fate of the universe.

References

- Penzias, A. A., & Wilson, R. W. (1965). A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s. Astrophysical Journal, 142, 419.

- Bennett, C. L., et al. (2013). Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results. Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 208(2), 20.

- Planck Collaboration. (2020). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6.

- Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press.

- Hu, W., & Dodelson, S. (2002). Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropies. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 40, 171-216.